| Contents

Introduction

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Introduction

After the defeat of Cestius the new war heroes -- those who had actually engaged in combat with the Roman forces -- were in control of affairs in Jerusalem. Exactly who these heroes were and what form the government took, Josephus does not say. At this point the already existing Sanhedrin, the council of citizens that had run local affairs in Jerusalem even under the Roman procurators, attempted to act as a national assembly, for Josephus refers to its authority several times in his bibliography: e.g., "the Sanhedrin of Jerusalem" in Life 12 61 and the "assembly of Jerusalem" in Life 38 190.

A possible exception is the mysterious John the Essene, whose leadership and military career belies one's image of the Essenes as nothing but peaceful monks spending their days copying scrolls at Qumran on the shores of the Dead Sea. Another omission is the leading Pharisee, Simon son of Gamaliel, who Josephus later describes as highly influential in the Jerusalem assembly. (Life 38 190) The regional commanders appointed at this time are

shown in the following table.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Who Were These People?

In addition, rebel factions held, somewhat independently of the central government, the fortresses of Masada, Machaerus and Cypros [2.485] What Josephus doesn't tell us is the names of the people who appointed the new generals, nor why those chosen arrived at those positions. We can try to surmise some of those involved. Prominent of those who had fought Cestius, hence may have been these leaders, included: relatives of King Monobazus of Adiabene; Niger of Peraea; Silas the Babylonian; and Simon son of Gioras (2.19.2 520). The only identifiable feature of these men is that they all originate outside of Jerusalem: the royal Adiabeneans; Niger a native of Peraea across the Jordan River and former governor of Idumaea; Silas perhaps a descendant of one of the Babylonian Jews who had been settled in Batanaea east of Galilee by Herod the Great; Simon, we find later, was a leader and possibly civil magistrate in the toparchy of Acrabatene. Does this mean the Jerusalem revolt was driven by

outsiders? That is doubtful -- more likely is it that Josephus did not

want to name any of his Jerusalem companions, many of whom he grew up with,

and so only identified non-Jerusalemites. And other than the Adiabeneans,

the men he named were all dead at the time he wrote the War; perhaps other

early leaders were not.

Josephus claims in the War he was alone appointed commander of the Galilees; however, in his later and more detailed autobiography, he only states that he was sent on a mission to Galilee with two other priests, his command only evolving over time. Josephus seems not to have explained that the original leaders made it a policy to appoint multiple commanders over each region, which would have been a wise precaution in any case given the inexperience in government and uncertain political loyalties of the principal men of Jerusalem. We see that two men were appointed commanders over Jerusalem, two or three over Idumaea, and, as just noted, three over Galilee. And these were all "additional generals" besides those unnamed ones who made the appointments. When John the Essene in western Judaea waged a campaign against Askelon he shared command with Silas the Babylonian and Niger the Peraean, two of the men whom we saw were named as major commanders against Cestius and, therefore, were likely among the real leaders afterwards. Similarly, although only a single man, John son of Ananias, is identified as governing the toparchy of Acrabatene and surrounding areas, there is evidence he shared this command with Simon son of Gioras, one of those prominent in the battle with Cestius, who had Acrabatene as a power base (2.22.2 652, 4.9.3 504); Prof. Goodman presents arguments that Simon had been an administrator of the area even before the war (The Ruling Class of Judaea, p. 163, 202ff). The use of multiple commanders may also reflect a compromise ensuring the representation of competing political parties in the government, as well as protecting the nation from the tyranny of a single ruler. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ananus son of AnanusThe former High Priest Ananus, who was appointed one of the supreme commanders of Jerusalem, had a taste for power, having tried to seize it illegally several years before.When he had been High Priest he had tried to act as governor after the sudden death of Festus, and at that time ordered killed James the brother of Jesus, for which he was deposed as high priest by Agrippa. Now he was finally leader of the city and Agrippa's military enemy. Ananus was the youngest of the five sons of the elder Ananus. Each of the sons had been high priest, for which the father was most fortunate, according to Josephus in Antiquities 20.9.1 197-203. But the youngest Ananus was "arrogant in character and exceptionally bold, and followed the school of the Sadducees, who, when they sit in judgment, are more heartless than any other Jews." The Ananus family had a history of acts

against lower class rebels -- in particular, against troublemakers from

Galilee, as seen in the following table.

With this background, it is no surprise that Ananus was suspicious of

the violent rebels among the lower classes. Josephus reports:

Ananus cherished the thought of gradually abandoning these warlike preparations and bending to a more useful course the seditious party and the madness of those called the 'Zealots'. (War 2.22.1 651)This also seems to have been Josephus' own position at the time. The man with whom Ananus shared power, Joseph son of Gorion, is mentioned nowhere else in Josephus' works. However, the Talmud refers to a Nakdimon ben Gurion, who was one of the three wealthy men who supplied Jerusalem with food and wood during the war. Perhaps Joseph and Nakdimon were brothers in a family whose wealth and pro-war leanings ensured them a political position. They mave have been of a different party from Ananus and provided a counterbalance to him. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Coining Money. Although Josephus does not refer to it, we know from archaeological finds that one of the first acts of the new government was the coining of money. Thick silver shekel and half-shekel coins labeled "Year One" have been found in quantity in Israel, and while there are fewer than these than the coins of the next two years, indicating it took some time to bring the mint into full production, they are not as rare as those of the fourth and fifth years of the war. The immediate production of these coins, which also bear the legend "Jerusalem the Holy," was doubtless for use in paying the Temple tax and purchasing sacrifices for the Temple, part of the support of the war effort by solidifying heaven's favor. For more information, see Ancient Jewish Coins Related to the Works of Josephus.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

All dates are estimates.

|

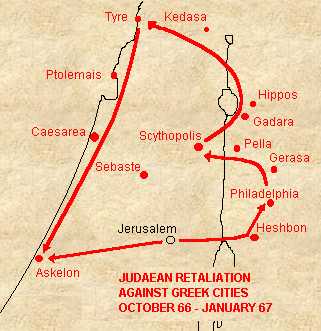

The

ethnic hatred that had long been a danger to the region exploded when Roman

authority in the region disappeared. At "the same day and the same hour"

as the slaughter of the surrendering Romans by the rebels in the initial

revolt, "as if by the hand of Providence" Syrians began to murder the Jewish

minority in their midst. (2.18.1 457) The Jewish reprisals against Syrian

towns were equally fierce, producing a cycle of murder and revenge of the

sort still familiar in the region in modern times.

The

ethnic hatred that had long been a danger to the region exploded when Roman

authority in the region disappeared. At "the same day and the same hour"

as the slaughter of the surrendering Romans by the rebels in the initial

revolt, "as if by the hand of Providence" Syrians began to murder the Jewish

minority in their midst. (2.18.1 457) The Jewish reprisals against Syrian

towns were equally fierce, producing a cycle of murder and revenge of the

sort still familiar in the region in modern times.